A recent study estimates that superbugs could potentially kill up to 40 million people by 2050.1 The World Health Organization deemed antimicrobial resistance (AMR) one of the top global public health threats. But what exactly are superbugs and how do they come to exist? To answer that we need to first understand what microbes are.

What Are Superbugs?

What Are Microbes?

Microbes are tiny living organisms found all around us. They can be found in the air, on surfaces, in our foods, and even inside our bodies. They are present in very large numbers in the human body. It is estimated that there are 30 trillion cells in the human body and 38 trillion bacterial cells.2 The beneficial microbes living inside your body work together to help your digestive, immune, and reproductive systems among other things. On the other hand, harmful microbes, known as pathogens can cause disease and illness among humans, plants, and animals. They can reproduce fast and spread easily, making them a threat to our health.

What Are Antimicrobials?

Luckily, many pathogens are treatable with drugs called antimicrobials. There are several types of antimicrobials. For example, antibiotics for bacteria, antifungals for fungi, antivirals for viruses, and lastly, antiparasitics for parasites. The war against infections (mainly bacterial infections) was thought to be over in the late 1920s with Alexander Fleming's discovery of Penicillin (a common antibiotic). This was followed by the discovery of multiple other broad range and specific antibiotics. However, with the spread and overuse of antibiotics in both humans and animals, microbes have become stronger than we thought. When microbes that were once susceptible to certain antibiotics, become resistant to them, they're referred to as superbugs.

Want to hear more from Norgen?

Join over 10,000 scientists, bioinformaticians, and researchers who receive our exclusive deals, industry updates, and more, directly to their inbox.

For a limited time, subscribe and SAVE 10% on your next purchase!

SIGN UP

What Are Some Common Superbugs?

1 in 5 cases of Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) caused by E.coli exhibit resistance to commonly used antibiotics such as ampicillin and fluoroquinolones. Klebsiella pneumoniae is a common intestinal bacterium that also shows resistance to beta-lactams, a widely used class of antibiotics. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a major concern due to its high mortality rates and resistance to many antibiotics used to treat regular staph infections.3 In Canada, between 2017 and 2021, nearly 20% of patients diagnosed with MRSA bloodstream infections died within 30 days of diagnosis.4 Some other common antibiotic-resistant bacteria include vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), multi-drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MDR-TB), and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE).5 AMR is a dangerous, and rapidly escalating global health crisis. Understanding more about how it occurs, can give researchers and medical personnel the ammunition they need to combat this crisis.

What Causes Antimicrobial Resistance?

Several factors contribute to the emergence and spread of AMR, with the misuse and overuse of antibiotics in clinical settings being the most significant concern. Antibiotics work by killing bacteria and/or stopping their reproductive cycle. The improper use of antibiotics begins when a patient misses one or more doses of their prescribed antibiotic or ends their treatment earlier than suggested. This causes the bacteria to start reproducing with a chance of becoming resistant to the residual antibiotic in the system. Overprescription of antibiotics for minor infections and misdiagnosis of viral infections is also accelerating AMR. AMR is particularly troubling in low-income communities and developing countries, where poor sanitation, lack of access to clean water, and limited vaccination programs are often the primary drivers of infections. In many cases, antibiotics are inappropriately prescribed for these infections, even when they are unnecessary, further exacerbating the problem. Moreover, in some regions, antibiotics are readily accessible without prescription, contributing to their misuse.6

Additionally, farming practices such as the use of nonessential antibiotics for growth and promotion in livestock contribute heavily to the spread of drug-resistant bacteria in both animals and humans. A study from 2015 estimated the total consumption of antibiotics in livestock in 2010 was 63,151 tons. They project that antimicrobial consumption in livestock will rise 67% by 2030.7 Agricultural antibiotic use causes antibiotic-resistant bacteria and genes to harbor in soil and eventually enter the water system as a pollutant.8 A study in 2009 found antibiotic-resistant genes and antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the tap water system.9 While antibiotics play a crucial role in supporting agricultural productivity and growth, their prolonged, low-dose usage may contribute to the rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), potentially burdening the healthcare system with millions in treatment costs.

How Does Antimicrobial Resistance Occur?

The mechanism of antimicrobial resistance is widely studied and categorized into two groups.

Intrinsic Resistance

The first way AMR occurs is through intrinsic resistance, which is the inherent ability of microorganisms to resist the effects of antibiotics. "For example, an antibiotic that affects the wall-building mechanism of the bacteria, such as penicillin, cannot affect bacteria that do not have a cell wall."10

Acquired Resistance

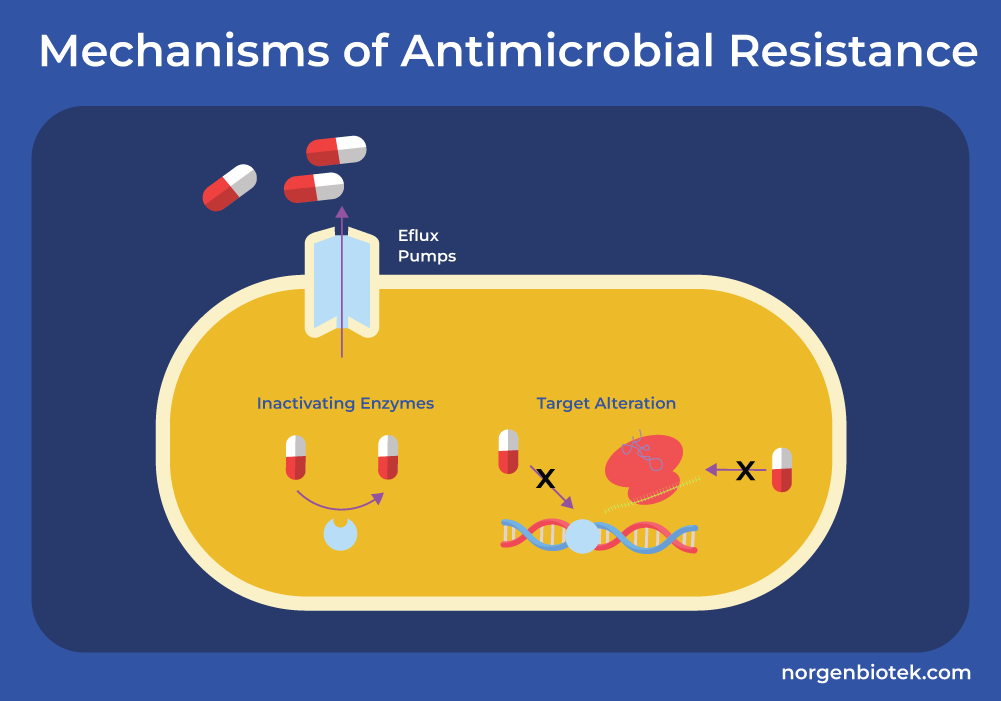

Secondly, acquired resistance is when initially antibiotic susceptible bacteria gain the ability to resist the effects of an antibiotic agent and proliferate and spread under selective pressure of that agent. Acquired resistance either requires the modification of existing genetic material (gene mutation) or the acquisition of new genetic material from another source (horizontal gene transfer). Acquired resistance genes may enable the bacteria to break down or chemically modify antibiotics, rendering them ineffective. They might develop or upregulate efflux pumps that actively transport antibiotics out of the cell, preventing the drug from reaching its intracellular target. They could modify the drug's target site, or produce an alternative metabolic pathway that bypasses the action of the drug.11

Gene Mutation and Selection

Approximately 1 in every 108–109 bacteria develop resistance when exposed to antibiotics through the process of spontaneous mutation. For example, E. coli develops streptomycin resistance at a rate of approximately 109 when exposed to high concentrations of streptomycin. Mutation is a very rare event, however due to the fast growth rate of bacteria it won't be long before resistance is developed in a population.12

Horizontal Gene Transfer

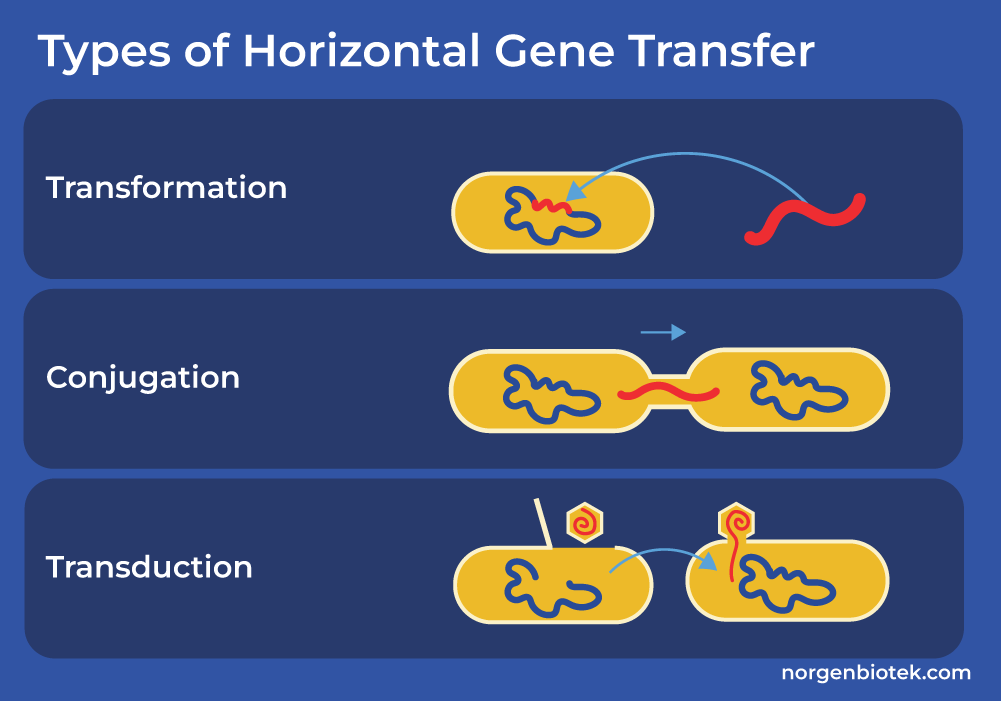

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is the movement of genetic information between more or less distinctly related organisms. Bacteria can develop resistance through the acquisition of new genetic material from other resistant organisms. HGT may occur between strains of the same species or between different bacterial species.There are three main mechanisms of HGT.

3 Types of Horizontal Gene Transfer

Transformation: Bacteria take up extracellular, naked DNA from the environment. Usually this DNA is present in the external environment due to the death and lysis of another bacteria.

Conjugation: The transfer of DNA via direct cell-to-cell connection. During conjugation, a gram-negative bacteria often uses an elongated proteinaceous structure called pilus, to transfer plasmid-containing resistance genes to an adjacent bacteria. On the other hand, the mating pair of gram-positive bacteria usually initiate conjugation by producing sex pheromones, which facilitate the clumping of donor and recipient organisms, allowing the exchange of DNA.

Transduction: The transfer of DNA via the use of bacteriophage. Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacterial cells and use them as hosts to multiply. After multiplying, these viruses assemble and sometimes remove a portion of the host's bacterial DNA. Later, when one of these bacteriophages infects a new bacterial cell, this piece of bacterial DNA may be incorporated into the genome of the new host. Many scientists take advantage of bacteriophages to introduce new genetic materials to various host cells.13 Here at Norgen Biotek we offer a variety of kits to isolate high quality bacterial DNA and RNA (Gram-positive and Gram- negative) from many different sample types including stool, cell culture, sand, urine, plasma, tissue and more.

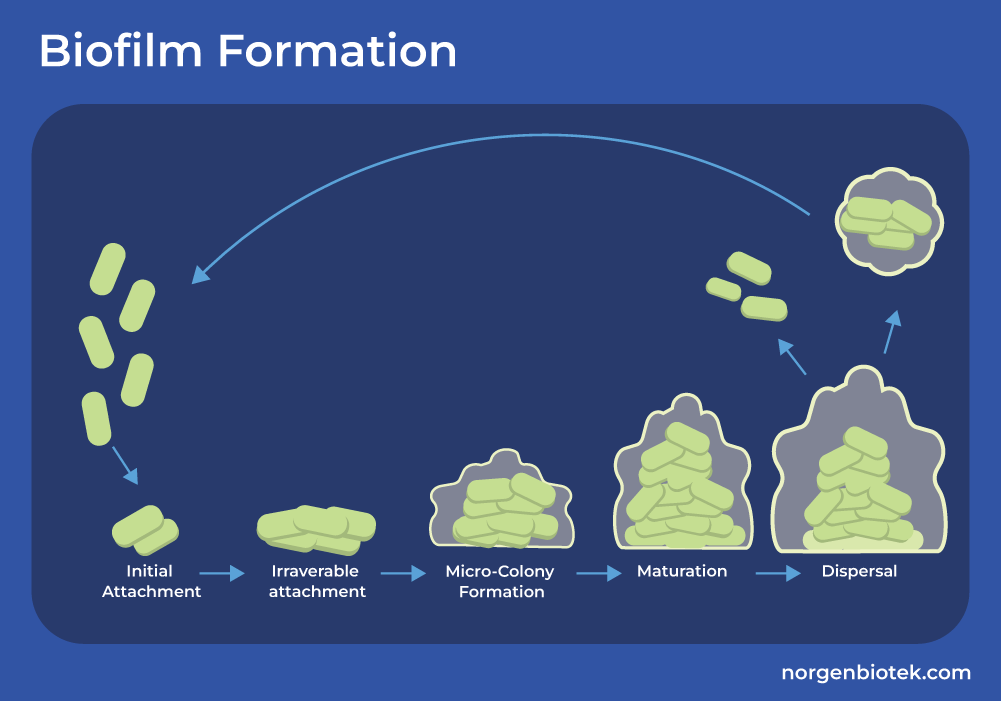

The Role of Biofilm in Antimicrobial Resistance

Pathogens can also form a protective barrier around them that makes treating them more difficult. This is known as a biofilm. A biofilm is a structure that begins forming when microbes adhere to a surface. They come together and produce a glue-like substance called extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) matrix. The microbes in the biofilm are able to continue reproducing and even join with other biofilm colonies. It's a complex structure that is known to significantly increase antimicrobial resistance. Bacteria that live in a biofilm can demonstrate a 10 to 1000-fold increase in resistance compared to the same bacteria that are not in a biofilm.14 Now that we know how antibiotic resistance spreads within bacterial species, let's take a look at how they deter the antibiotic and evade its effects.

Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance

In any battle, the side that understands its opponent best always holds the advantage. Similarly, the more we know about antibiotic-resistant bacteria, the better we can treat them. With a vast array of bacteria exhibiting resistance, each employing unique strategies, understanding the mechanism of resistance is crucial in creating new antibiotics to treat these formidable pathogens. Check out this quick video discussing the key mechanism of antimicrobial resistance.

Efflux Pumps

One of the key mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in gram-negative bacteria is through efflux pumps. These protein pumps are designed to eliminate any toxic substances (such as antibiotics) from within the bacterial cell.15 They decrease the intracellular concentration of antibiotics, diminishing their efficacy and reducing their ability to target critical cellular processes.

Enzymatic Inactivation

β-lactams (also known as penicillins), one of the most widely used groups of antimicrobials, contain a four-sided β-lactam ring. Bacteria have evolved several resistance mechanisms to these drugs. The most common strategy involves β-lactamase enzymes, which hydrolyze the β-lactam rings, rendering the antibiotic ineffective. While β-lactamase inhibitors, such as clavulanic acid and avibactam, have been developed to counteract these enzymes, newer and more resilient bacterial strains such as carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) pose significant challenges.16

Target Site Modification

β-lactamases are not the only method employed by bacteria to resist the effects of β-lactams. Gram-positive bacteria alter the structure or number of penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) which either decreases the amount of drug that can bind to the target or completely inhibits the binding.16 PBPs are proteins of the bacterial cell membrane that are involved in the biosynthesis of the cell wall known as peptidoglycans (PG).17 Gram-negative bacteria have intrinsic resistance to drugs like vancomycin which are glycopeptides that inhibit cell wall synthesis, and daptomycin which are lipopeptides that depolarize the cell membrane. Other bacteria can gain resistance to glycopeptides through the alteration in the structure of PG precursors. This reduces the binding ability of glycopeptides. On the other hand, gene mutations alter the charge of the cell membrane which inhibits the binding of calcium, an essential step for the function of daptomycin. This inhibits the binding of daptomycin and its ability to depolarize the cell membrane.16

Discovery of New AMR Mechanisms

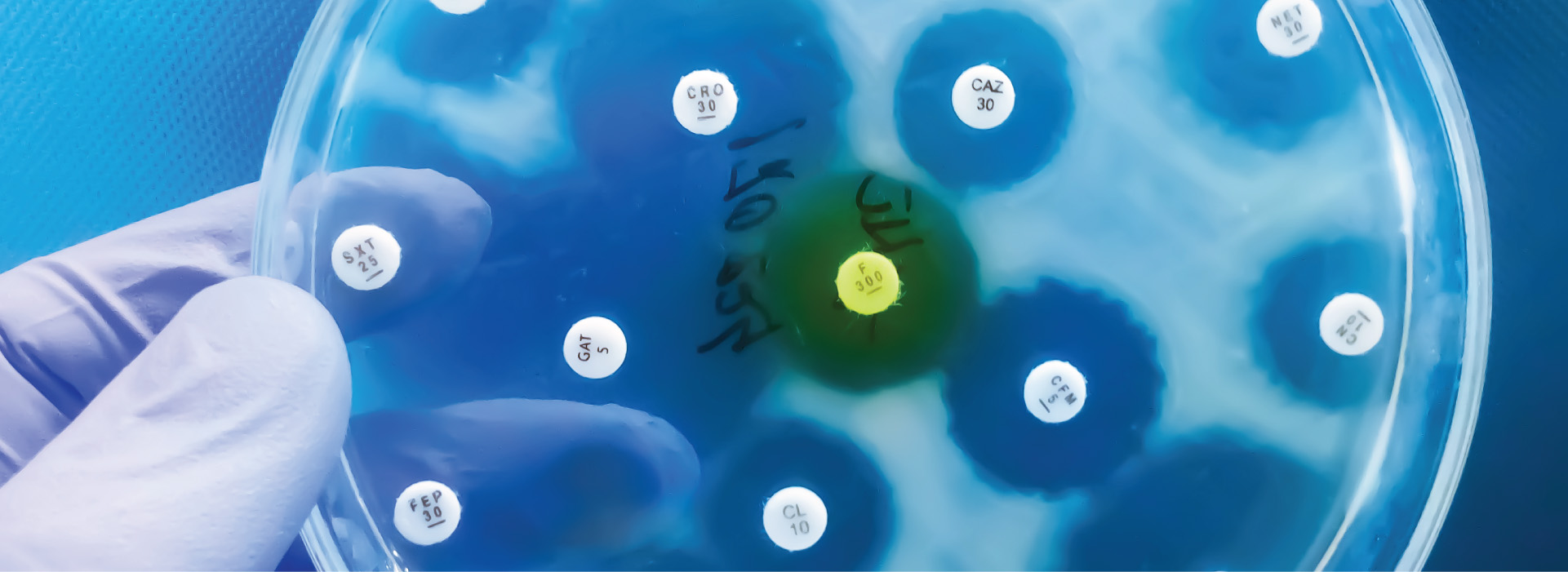

There are likely numerous resistance mechanisms that remain undiscovered. Studying the mechanisms of AMR involves a combination of molecular, microbiological, and bioinformatics approaches. Researchers use various methods to identify, characterize, and understand how bacteria develop and spread resistance. Researchers collect clinical bacterial isolates from patients, animals, or the environment to monitor resistance trends. In addition, phenotypic testing such as standard antimicrobial susceptibility tests (e.g., disk diffusion, broth microdilution) can be used to identify resistant strains. Alternatively researchers can use genotypic analysis such as molecular methods (e.g., PCR, whole-genome sequencing) screen for known resistance genes and mutations.18

The most common molecular method used by clinical laboratories to understand resistance mechanisms underlying an observed phenotypic resistance is the PCR-based approach including conventional PCR, real-time and qRT-PCR. In this approach genes known to be involved in the resistance are amplified and sequenced. Then these sequences are compared to the sequences of wild type strain and possible mutations are found. qRT-PCR can be used to study and compare the expression levels of these resistance genes between mutant strain (showing resistant phenotype) and wild-type strain.18

Functional genomics can be used to identify new antibiotic-resistance genes encoding for an enzyme based on their function. In this technique fragments of DNA are extracted and a specific library of a homogeneous size is created. This library is then cloned into an expression vector, which is then screened depending on the studied antibiotic.19

The advancement of genomic techniques that enable the study of diverse environmental microbial communities without the need for cultivation has been instrumental in uncovering novel resistance pathways. Moreover, cultivating harmful bacteria poses significant risks to scientists handling them, necessitating advanced equipment and stringent safety protocols. Modern sequencing technologies offer significant potential in addressing the escalating challenge of antibiotic resistance. Metagenomic sequencing, in particular, has revealed an extensive reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes within the complex microbial communities inhabiting the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and animals, as well as natural environments such as surface water and soil. This has been possible due to the rapid decline in sequencing costs, leading to the identification of an increasing number of resistance genes. The integration of genomic analysis with continuously updated databases presents a powerful and emerging approach, granting access to vast amounts of information and enhancing our ability to study antimicrobial resistance while providing deeper insights into bacterial behavior.20

The Role of Gene Sequencing in AMR

The prediction of new antimicrobial resistance through genome sequencing can be accelerated using prior knowledge of all variables that can contribute to phenotypic resistance, such as inactivating enzymes, porin mutations, influx system alterations, binding site mutations, gene inactivation, and promoter mutations. The sequence-based identification of known resistance markers represents only a small fraction of the resistance spectrum and transcriptome analysis could provide a more comprehensive phenotypic profile. Bacterial expression patterns can vary significantly in the presence or absence of antibiotics, offering the potential to detect resistance at the RNA level as a response to environmental stressors.21

Transcriptome analysis presents a promising alternative to solely relying on genome sequencing for resistance gene identification. High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), a cutting-edge technology, utilizes deep sequencing techniques to analyze an RNA population that has been converted into a library of complementary DNA (cDNA) fragments. These sequences are then bioinformatically assembled to reconstruct the complete transcriptome and quantify gene expression levels with high precision.22

The study of RNA provides a viable alternative to the research of genetic mechanisms underlying antimicrobial resistance. For instance, colistin, a polymyxin antibiotic used to treat infections caused by susceptible Gram-negative bacteria, has been the focus of recent research combining genome sequencing with transcriptional profiling via RNA-Seq. This approach led to the identification of crr genes, previously described as uncharacterized histidine kinases, as additional regulators of colistin resistance. These findings expand the repertoire of genes involved in colistin resistance and underscore the diverse ways in which bacteria can respond to antimicrobial peptides.23

Streamlined Solutions for AMR Research

Norgen Biotek provides full workflow solutions to support scientists in their antimicrobial resistance (AMR) research, covering every step from RNA and DNA preservation to isolation and sequencing. Norgen's innovative preservatives offer researchers a fast and convenient method for sample collection, preservation, and room temperature shipping. These preservatives render samples non-infectious, making them an ideal choice when handling AMR strains.

In addition, Norgen Biotek offers a range of high-performance isolation kits designed for the extraction of high-quality DNA, RNA, or both, enabling seamless downstream applications such as qPCR and next-generation sequencing (NGS). The company also provides a variety of PCR products, including PCR Master Mix, DNA Ladders, and PCR Purification Kits to streamline laboratory workflows. Furthermore, Norgen Biotek delivers comprehensive NGS services, including metagenomics, small RNA (microRNA) sequencing, and total RNA (mRNA) sequencing. These services are complemented by advanced bioinformatics analyses, delivering high-quality, ready-to-publish data to accelerate scientific discoveries.

How to Prevent Antibiotic Resistance

Not that we know how AMR works, let's take a look at what we can do to prevent its spread. The first step in preventing the spread of AMR is to prevent the spread of infections altogether. This includes staying home when you are sick, maintaining proper hygiene, and keeping up-to-date with vaccines among other precautions. The government of Canada says, the responsible use of antimicrobials, namely antibiotics, is crucial to prevent the spread of superbugs. Overuse and misuse of antibiotics are some of the leading causes of AMR development.24 According to a 2017 study, “Up to 40% of antibiotic prescriptions for these conditions are unnecessary”25 This not only creates more mutant bacteria, but it is also detrimental to the gut microbiome of patients as the antibiotics hurt both good and bad bacteria. It is important that doctors diagnose bacterial infections correctly and only prescribe antibiotics when needed. Patients must also part-take in the responsible consumption of antibiotics. Sharing medication, flushing them down the drain, not finishing the course of treatment, or not taking the medication as directed can also cause AMR to spread rapidly. We must do our part to prevent the development of superbugs.

The Future of Antimicrobial Resistance

Pathogens are constantly evolving, finding new ways to grow stronger and outsmart our treatments. As they adapt and become more resistant, the challenge to control infections becomes even greater. But there's hope! Innovative research is paving the way for breakthroughs that could tip the scales back in our favor. By staying one step ahead of these crafty microbes, scientists are unlocking new ways to combat infections and protect global health. That's why Norgen is here to help every step of the way.

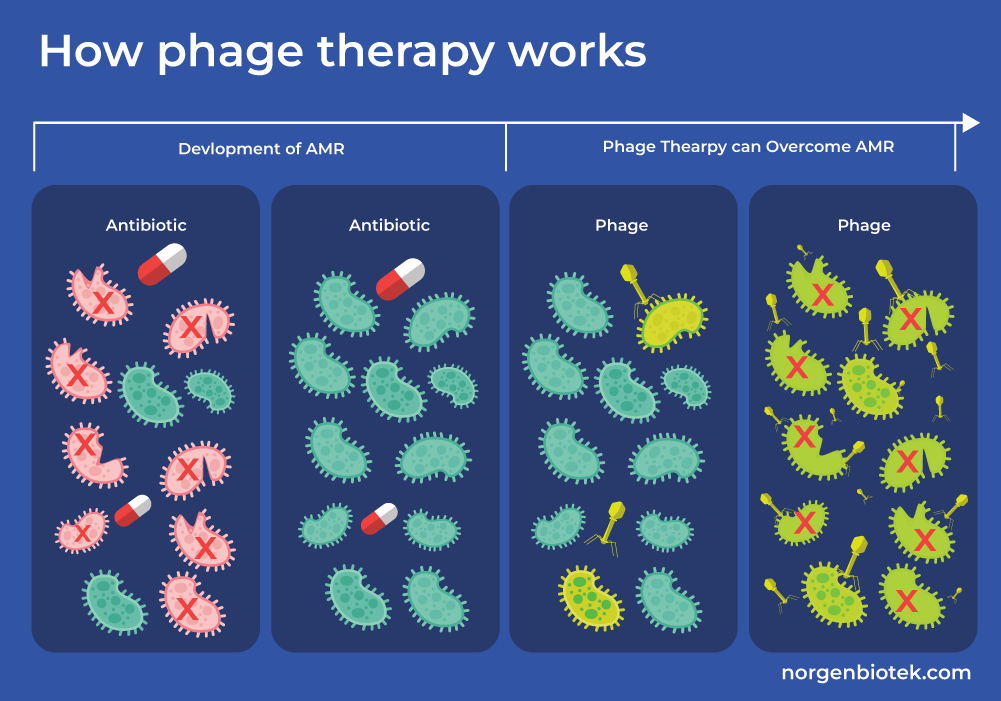

Phage Therapy

Phage therapy is a promising alternative to antibiotics in the fight against AMR. Bacteriophages, also known as phages, are viruses that infect bacteria and replicate within them causing cell lysis and eventually cell death. Unlike traditional antibiotics, phages specifically target and kill bacteria, offering a precision approach to treating infections without harming beneficial microbes. This targeted action makes phage therapy a valuable tool in addressing multidrug-resistant pathogens, where conventional treatments often fail.

To advance research in phage therapy, having reliable tools for isolating and studying bacteriophages is crucial. Norgen Biotek's Phage DNA Isolation Kit simplifies this process by providing an efficient method to isolate high-quality phage DNA.

Phage Therapy Research Highlight

Researchers from Bu-Ali Sina University characterized a new lytic bacteriophage isolated from wastewater found in poultry slaughterhouses to evaluate its potential as an alternative treatment to antibiotics. They assessed Escherichia phage VaT-2019a isolate PE17 and a new page, Escherichia phage AG-MK-2022. Basu's host range, environmental stability, genetic composition, and bactericidal efficacy against 100 multidrug-resistant avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (MDR-APEC) strains were evaluated.

From the morphology of Escherichia phage AG-MK-2022. Basu, the research team identified its family to be Myoviridae. More importantly, they conducted a phage genome analysis using Norgen's Phage DNA Isolation kit and found that it contains no antibiotic resistance gene, mobile genetic elements, and E. coli virulence-associated genes. They also evaluated the stability of the phage and found that it is stable in temperatures between 4°C–80°C, pH between 4–10, and NaCl concentrations between 1–13%. These findings indicate that Escherichia phage AG-MK-2022. Basu "may safely be used as a biocontrol agent". It should be noted that "more work, such as whole genome sequencing of the isolated phage, is necessary to achieve more information regarding its safe use".26

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses an undeniable threat to global health, with the threat of superbugs becoming increasingly alarming. The misuse and overuse of antibiotics, combined with natural microbial evolution, have created a challenge that demands urgent action.

Innovative solutions like phage therapy offer hope, demonstrating that through advanced research and cutting-edge tools, we can outpace these resistant pathogens. Norgen Biotek is committed to supporting researchers in this endeavor by providing reliable products, such as the Phage DNA Isolation Kit, to drive breakthroughs in AMR combat strategies.

The future of global health depends on staying ahead of these evolving threats. By investing in research, responsible antibiotic usage, and technological advancements, we can turn the tide on antimicrobial resistance.

FAQs

What is antibiotic stewardship?

According to the CDC, antibiotic stewardship is the surveillance of antibiotic prescription and usage. Antibiotic stewardship programs all around the world coordinate the appropriate usage of antibiotics in order to limit the spread of AMR.

Does hand sanitizer cause superbugs?

No, the use of hand sanitizers does not cause the emergence of superbugs. Hand sanitizers are ethanol based, which quickly kill the bacteria by destroying their cell wall, whereas antibiotics slow the growth of bacteria. Hand sanitizers act fast and evaporate before the bacteria have a chance to develop resistance.

What is the superbug MRSA?

MRSA stands for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. This is a type of bacteria that is resistant to methicillin, one of the most commonly used antibiotics for staph infection. MRSA is a potentially deadly bacteria and there are only a few antibiotics that can treat serious MRSA infections.

Does bleach cause superbugs?

No, bleach does not contribute to the emergence of superbugs. Bleach kills microbes by disrupting their cellular structure. It's a fast-acting disinfectant that allows no time for microbes to develop resistance.

Can strep be antibiotic resistant?

Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as group A streptococcus, is the bacteria that causes strep throat. Although this bacteria is not resistant to penicillin or cephalosporins, its resistance to azithromycin, clarithromycin, and clindamycin is well known.